|

Boston’s First Skyscraper In 1893 Easton notable Frederick Lothrop Ames constructed the first skyscraper in Boston. It is the second tallest masonry load bearing-wall structure in the world. It wasn’t replaced as the tallest building in Boston until 1915 when the Custom House Tower was built. The Ames Building is located at 1 Court Street and today serves as dormitories for Suffolk University students. Not surprisingly, the building was designed in the Richardsonian Romanesque style by the firm of Shepley, Rutan, and Coolidge. For many years the building served as the corporate headquarters of the Ames Agricultural Tool Company as well as other businesses. It held an important place in Boston’s financial community. One of its more recent incarnations was as a luxury boutique hotel, the Ames Boston Hotel. In 2018 the building was ranked 87 out of 100 on Boston Magazine’s list of the best buildings in Boston. It had already been added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 and later designated as a Boston Landmark. You can clearly see the influence of Richardson who passed away in 1886. His style was continued by his associates. The building is 14 stories tall and faced with sandstone and granite. Note the arches and Romanesque columns. More information can be found by clicking on the links below. Additional pictures and written materials from 2018 compiled by our Board Member Steve Anderson.

0 Comments

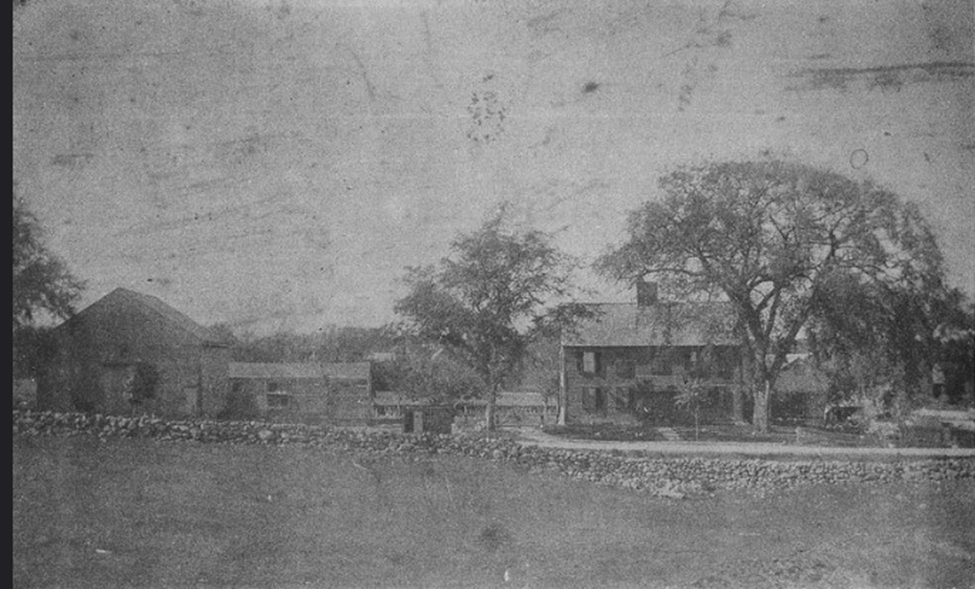

Do stones feel? Do they love their life? Or does their patience drown out everything else? Do Stones Feel by Mary Oliver Once you start looking, they are everywhere. The stone walls. And more. All kinds of purpose-built stone structures. In early days in Easton, stone, dependable and relatively permanent, was used to mark boundaries and show ownership. As early as 1713 there was a boundary dispute over the northern line of the Taunton North-Purchase. The marker was “a heap of stones on a great rock.” (Chaffin) Early colonists, everywhere in New England, acquired land, marked the land, sometimes with elongated upright stone or pillars. Root cellars like the potato cellar at Sheep Pasture and one (I believe) on the original Spring Hill property were built for storing root crops for human consumption or animal feed over the winter. These particular cellars were built relatively late (!890’s) and were part of planned estates but still represent the concept. Early mill industries needed stone and/or waste stone to create dams. A walk through certain woods today will reveal many small dams, or channels, created at various times to direct water. In the 1820’s and 1830s, in relatively prosperous times,“tossed walls were improved to classical double walls.” (Thorson) Large boulders were moved if necessary- blown up, buried, or moved with devices. In Easton, as elsewhere, graveyard walls were built with more care than farmyard walls. Here is a current photo of a bit of the wall and an entrance to the Washington Street Cemetery. Washington Street Cemetery, 1796. The Hayward House at 49 Poquanticut Ave, 1803, illustrates the use of stone in the gate that also serves as a property marker. Photo by Kathryn Grover and Neil Larson, Massachusetts Historical Commission, info., Easton Historical Society. The Keith House, 29 Highland Street. Easton Historical Society. Note the beautiful wall.

There have been some stone remains I’ve found in the woods that are a mystery to me. I’m doing some personal research on older stone structures in town. If anyone reading this has any information about old cellars, ruins, or anything interesting, please let me know. I am particularly interested in the Wheaton Farm property, of which I know very little. I am looking for more ‘everyday’ stone structures, not estate structures. Thank you in advance for any tips! Sources: Root Cellars in America. https://www.stonestructures.org/html/root_cellars.html Stone by Stone, The Magnificent History of New England’s Stone Walls, Robert M. Thorson, 2002. wbur.org 3/3/2024, podcast Easton Historical Society Anne Wooster Drury [email protected] |

Author

Anne Wooster Drury Archives

June 2024

Categories |

Easton Historical Society and Museum

PO Box 3

80 Mechanic Street

North Easton, MA 02356

Tel: 508-238-7774

[email protected]