|

Hello everyone, I would like to introduce you to Bryan Casey. Bryan is entering his freshman year of college and has interests in history and political science. He is interning with us this summer, and will be researching the Civil Rights movement, especially in the Easton area and Massachusetts in general. Attached is a brief questionnaire that Bryan put together. He would very much appreciate your reviewing it, and hopefully, respond to it. You can respond to individual questions, or use it as a guide for a more general response. You may feel free to either disclose your personal information or keep your answer confidential. This form, or just your experiences, can be sent to us by return email or if you prefer, by letter mailed to us at P.O. Box 3, North Easton, MA. We would appreciate hearing from you by August 15th so Bryan will have an opportunity to read through all your responses. This is an important period in the history of our nation as well as our town. Thank you for considering this and adding personal experiences to our knowledge base. Best regards, Frank -- Frank T. Meninno Curator, Easton Historical Society and Museum 508-238-7774 www.eastonmahistoricalsociety.org

0 Comments

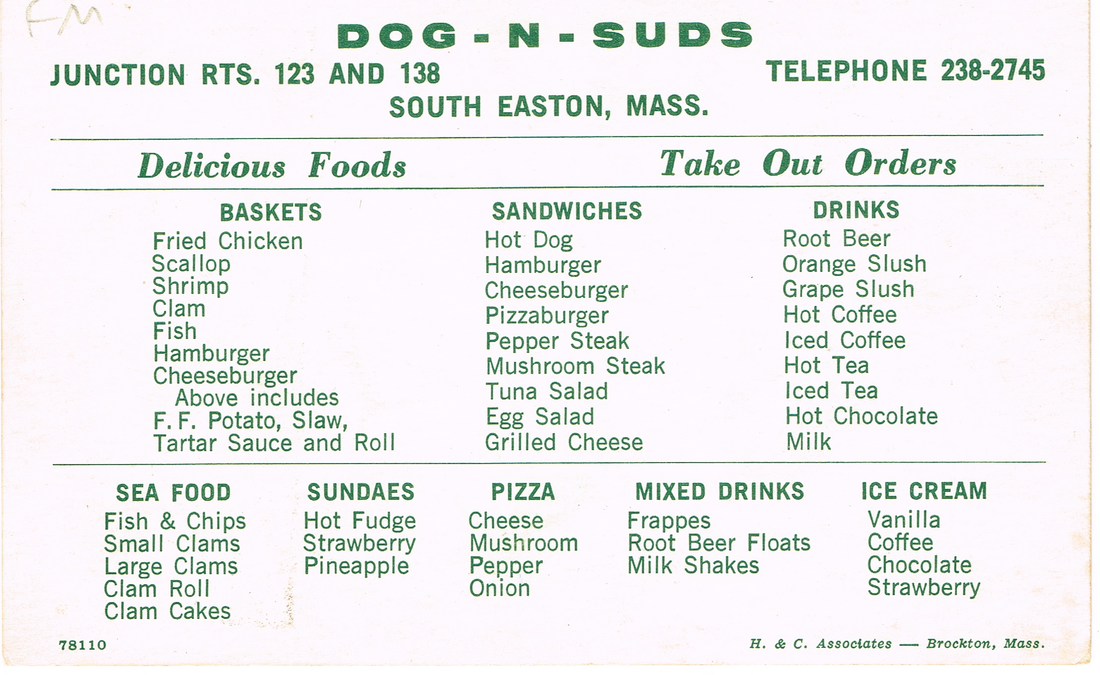

Hello my fellow history lovers! Another warm Saturday morning is a nice start to the day. Our second heat wave is just around the corner as temps get back into the 90’s early next week. Drought conditions are showing up all around us with wilting trees, dry gardens, and lots of brown lawns occupying the landscapes. I received a number of great comments from last week’s column, and a lot of guesses on my question: What does R.P.O. stand for? The correct answer is Railway Post Office. Mail that was processed on a train was marked with this distinctive cancellation as early as the 1840’s. If you were correct, good for you! Some things always seem to go together: sticks and stones, bat and ball, beer and wine, bacon and eggs, you get the idea. One of my favorites is our then and now photo for a hot summer day, a place you could pull up your car, roll down your window, and get a cold drink with a wonderfully frothy head: Dog ‘n’ Suds! The Dog ‘n’ Suds chain began in Illinois in 1953, the brainchild of Don Hamader and Jim Griggs, two music teachers at the University of Illinois. The chain quickly grew throughout the midwest region before finding its way to both coasts of the United States. In 1963, our own Dog ‘n’ Suds restaurant opened at the corner of Belmont and Washington Streets. It immediately became a go to place for great root beer and sandwiches. My own memory of that place is limited. We did not go very often, but I do remember my father driving all of us there for a treat now and then. Parking under the awning, we waited for someone to come out and take our order (maybe on roller skates?) and waited just a bit for our food to arrive. Out it came, on a special tray with brackets that allowed it to straddle a partially rolled down car window. We always enjoyed the ice cold root beer, a hamburger, and if I remember right, a delicious fish sandwich loaded with tartar sauce! Going there was truly a special event for our family. Unfortunately, Dog ‘n’ Suds had a short run here. A look at the Easton Town Reports shows the issuing of Victualer’s Licenses. As I said above, the first license was granted in 1963. The last license, a special permit for Sunday operations, seems to be the one issued in 1971, and perhaps, 1972. I do not know the name of the people who owned the franchise. The last root beer stand I remember in this area was a Henry’s Root Beer on Route 138 in Taunton, and I think that must have closed in the 1980’s. Dog ‘n’ Suds still exists in the midwest, with 20 locations in 7 states. If you are traveling through Illinois, Indiana, Ohio and a few other states, you might get lucky enough to stop at one and enjoy the excellent root beer that made them so famous. Below are a few photos for you. The first two are from the mid-1960’s, and are taken from an advertising postcard. In the first image, we are looking at Dog ‘n’ Suds from the west side of Washington Street, looking northeasterly across the intersection with Belmont Street. Recognize any of the cars? The second image, from the card’s reverse, lists the food and drink items that were available – more of a selection than I remembered! The third image is the location today. Once Dog ‘n’ Suds was out of business, a bank occupied this location for a number of years. That later gave way to the small plaza at the site today. And last, but not least, enjoy a photo of one of those great Dog ‘n’ Suds mugs now in our collections. Sorry it is not full of root beer! Until next week, happy sipping,

Frank Happy Saturday! Last week I was preparing for some hot weather. It arrived right on time! Today marks five consecutive days of hot and humid weather, and it looks like the rest of the weekend will hold true to that. We might see our first triple digit temps of the summer on Sunday. Sounds like a good nap day to me! One of the early lessons I learned as an historian is that you should always look on both sides of a sheet of paper. Many times, when looking at an old photo and wondering who or what is in the image, a careful look at the reverse side can reveal old notes that will provide my answer. Today’s look back was one of those instances where I saw a photo, and by habit, looked at the back of the paper. That led to some detective work, and the result is a sweet story. Here is a postcard of Pine Grove Poultry Farm, currently the area of 537 Turnpike Street, South Easton, across from Golf Country. The postcard is a fine photo of one of the many poultry farms that once dotted Easton’s landscape, and in and of itself, is a terrific historic piece. Of course, I turned the card over to see if there were any notes written on the back. Here is what I found! At first glance, I noticed an R.P.O. cancellation mark, a 1911 date, and who the card was addressed to. The publisher of the card, Webster W. Bolton, is also prominent. The message is not as easy to read. I immediately thought this might be a cypher, which was a popular fun code between two people, but a second look revealed to my (un)trained eye that this could be written in shorthand! Why would someone write to someone else using shorthand? Was someone having some fun with the recipient, or was something else at play? Everett A. Dunn (1885-1953) was an Easton resident who was working in 1911 for the old Brockton Street Railway trolley. As noted on the bottom of the card, he wore Motorman badge #622. The card was addressed to him at his place of work, the old Campello (Brockton) Car Barn. We know the recipient, and many of us remember his family. But we still had no clue as to the identity, or the subject matter, of the sender. I shared the card with Arielle Nathanson, our Archivist intern, who also became quite interested in this. Our intrepid intern-turned-detective began the first steps in unraveling our mystery. Using some online shorthand sources, she tried her best to decipher the note. Some of the symbols were close to shorthand still in use today, while others had no correlation. Arielle suggested posting this to Reddit, a web-based community of people with a variety of interests, to see if someone might solve our mystery. A few days later, we had our answer! Thanks to Reddit user Beryl Pratt, www.long-live-pitmans-shorthand.org.uk, a translation came through our email. Pitman’s Shorthand was created by Englishman Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897) back in 1837 as a way to capture the spoken word phonetically rather than with an actual longhand written transcription. The system is still in use in the U.K., and still somewhat in use in the States. When Arielle began trying to transcribe the note before sending it off to Reddit, she was able to find a name: Amy. A clue? Yes, and no. Yes, we had a name. However, around the time this note was written, there had been several small improvements to the Pitman system, and in the first part of the 20th Century, the writer was using a combination of both the “old” Pitman and the “new” Pitman shorthand. When we got our translation, things finally came together. The bulk of the note is a thank you for a favor provided by Mr. Dunn. “I thank you very much for helping us to catch the car this morning. Can’t you read French and German? All right, I will write shorthand to you now. I am very busy in the office now so that I hardly have any time to myself. I am visiting a friend in Dorchester.” It was signed “Sincerely Yours, Emma.” Using the expert translation from our friend in this sub-Reddit group, the sender’s name was correctly translated as Emma. Emma L. Howard (1888-1972) was an Easton girl who was working in an office in Boston (where the card was mailed from), and evidently our Mr. Dunn was of great service in helping her get to the right trolley to see her friend near Boston. She expressed her appreciation playfully with a nicely written thank you. But why write such an innocent note in shorthand? If you look at the lower left of her note, there is another small section of shorthand written. It is there that the story finally comes together. Emma states to Everett: “You can’t keep me guessing any longer.” It seems Everett and Emma had at least a passing friendship at that time which was ripe for blossoming. Indeed this is a note between two people who, in just a few years, would become husband and wife. Everett finally asked Emma to join him in the grand institution of matrimony, and the happy couple were married on September 16th, 1915. They settled at 49 Highland Street, in an old cape on the Williams farm, and there they raised three children (Mildred Cushman, Everett A. Dunn, Jr., and Arthur H. Dunn.) The house was built before 1825, as it appears on the 1825 map as S. Williams. It was still in the Williams family up to the early 1900’s, at which time it appears to have been purchased by the Dunn’s where they lived out the rest of their years. Now we have the answer to our mystery note! Who doesn’t like a love story with a happy ending? At first glance, I noticed an R.P.O. cancellation mark, a 1911 date, and who the card was addressed to. The publisher of the card, Webster W. Bolton, is also prominent. The message is not as easy to read. I immediately thought this might be a cypher, which was a popular fun code between two people, but a second look revealed to my (un)trained eye that this could be written in shorthand! Why would someone write to someone else using shorthand? Was someone having some fun with the recipient, or was something else at play? Everett A. Dunn (1885-1953) was an Easton resident who was working in 1911 for the old Brockton Street Railway trolley. As noted on the bottom of the card, he wore Motorman badge #622. The card was addressed to him at his place of work, the old Campello (Brockton) Car Barn. We know the recipient, and many of us remember his family. But we still had no clue as to the identity, or the subject matter, of the sender. I shared the card with Arielle Nathanson, our Archivist intern, who also became quite interested in this. Our intrepid intern-turned-detective began the first steps in unraveling our mystery. Using some online shorthand sources, she tried her best to decipher the note. Some of the symbols were close to shorthand still in use today, while others had no correlation. Arielle suggested posting this to Reddit, a web-based community of people with a variety of interests, to see if someone might solve our mystery. A few days later, we had our answer! Thanks to Reddit user Beryl Pratt, www.long-live-pitmans-shorthand.org.uk, a translation came through our email. Pitman’s Shorthand was created by Englishman Sir Isaac Pitman (1813-1897) back in 1837 as a way to capture the spoken word phonetically rather than with an actual longhand written transcription. The system is still in use in the U.K., and still somewhat in use in the States. When Arielle began trying to transcribe the note before sending it off to Reddit, she was able to find a name: Amy. A clue? Yes, and no. Yes, we had a name. However, around the time this note was written, there had been several small improvements to the Pitman system, and in the first part of the 20th Century, the writer was using a combination of both the “old” Pitman and the “new” Pitman shorthand. When we got our translation, things finally came together. The bulk of the note is a thank you for a favor provided by Mr. Dunn. “I thank you very much for helping us to catch the car this morning. Can’t you read French and German? All right, I will write shorthand to you now. I am very busy in the office now so that I hardly have any time to myself. I am visiting a friend in Dorchester.” It was signed “Sincerely Yours, Emma.” Using the expert translation from our friend in this sub-Reddit group, the sender’s name was correctly translated as Emma. Emma L. Howard (1888-1972) was an Easton girl who was working in an office in Boston (where the card was mailed from), and evidently our Mr. Dunn was of great service in helping her get to the right trolley to see her friend near Boston. She expressed her appreciation playfully with a nicely written thank you. But why write such an innocent note in shorthand? If you look at the lower left of her note, there is another small section of shorthand written. It is there that the story finally comes together. Emma states to Everett: “You can’t keep me guessing any longer.” It seems Everett and Emma had at least a passing friendship at that time which was ripe for blossoming. Indeed this is a note between two people who, in just a few years, would become husband and wife. Everett finally asked Emma to join him in the grand institution of matrimony, and the happy couple were married on September 16th, 1915. They settled at 49 Highland Street, in an old cape on the Williams farm, and there they raised three children (Mildred Cushman, Everett A. Dunn, Jr., and Arthur H. Dunn.) The house was built before 1825, as it appears on the 1825 map as S. Williams. It was still in the Williams family up to the early 1900’s, at which time it appears to have been purchased by the Dunn’s where they lived out the rest of their years. Now we have the answer to our mystery note! Who doesn’t like a love story with a happy ending? The Williams / Dunn House at 49 Highland Street. This was razed and replaced by a new house a few years ago.

By the way, here is a mystery for you to solve: The cancellation is stamped R.P.O. What does that stand for? Until next week, stay cool, and stay well, Frank Happy Saturday everyone! Great summer weather continues today, and the week has been sunny and very warm. The cool nights sure make sleeping an easy task. It is July however, and soon those three “H’s” of summer - hazy, hot, humid, will make their appearance. Our Open House last week was a huge success! Ed Hands led a great tour to some of the landscapes done by Frederick Law Olmsted, and visitors to the Museum looked at a selection of photos from Olmsted’s work in and around North Easton. Many thanks to Ed for his informative tour, and to the Ames family for allowing us over the bridge to see the wonderful vistas at “Langwater.” In our look back in time today we journey over dirt roads to that village of South Easton. From the Museum, a ride down Center Street to Short Street to Central Street down to the old Turnpike (now Washington Street) brings us down to the former Morse Thread Factory site. A turn northerly on Washington Street finds us in the immediate vicinity of the site once occupied by several generations of the Swan family. Dr. Caleb Swan’s house (razed in the very early 1960’s) once stood very near the site of the current Easton Marketplace, and he owned a second home just up the road past what is now Belmont Street. That home also no longer stands, torn down in the 1980’s. Dr. Swan also owned a third home, still standing at 579 Washington Street, and it is there that we will focus our attention. Dr. Caleb Swan (1793-1870) was a well-connected country doctor. Over the years he built up a faithful following as he treated people with homeopathic medicines. He also was active politically, serving on the Easton School Committee for fourteen years beginning in 1827. He also supported temperance movements, and often spoke about the need for good public education. He was a strong supporter of the Free Soil Party, and even though he ran unsuccessfully for the offices of Congress and Governor, the party did well, becoming the dominant political party in town by 1852. However, the rise of a new party, the Know-Nothing Party in 1854, soon erased any gains. An abolitionist before this, Swan became an even more passionate abolitionist following the wins by the Know-Nothings. He attended and spoke at anti-slavery rallies in Taunton and other places. He made no secret of his feelings on slavery, and he followed that up by taking an active part in an all-important part of history. He was a conductor on the Underground Railroad. There has always been a feeling that Easton had a number of people involved in helping escaped slaves. In North Easton, Oakes Ames and his brother Oliver 2nd may have helped slaves who were “following the North Star” by providing temporary shelter, food, and clothing. Stops on the Underground Railroad were supposedly located along Bay Road, Poquanticut Avenue, and undoubtedly other places in town, where a network of people quietly provided safe harbor and hope to those who needed it most. In South Easton, the Morse family made trips south to purchase cotton for their thread business, observing first-hand the institution of slavery. It is thought that they helped to secure freedom for some slaves by hiding them in loads of cotton that were being shipped north. Unfortunately for us, we have no hard evidence to educate us on the activities of these abolitionists. Except for one small mention, and that involved our Dr. Swan. Daniel C. Lillie (1829-1911) lived in Center Street. History loves a good writer, and he was one who took time to record his observations in diaries. He also contributed his skills to the old Easton Journal, where in 1886, he wrote a column simply titled “Easton Twenty years Ago” (he also wrote about “Easton Forty Years Ago.”) One of his columns specifically mentions that Dr. Swan did indeed harbor fugitive slaves in his house, providing a safe place to rest, food, clothing, and some money to help runaway slaves on their way to Canada! Finally, we have a first-hand account, albeit brief, of people in Easton actively participating in the Underground Railroad. However, Dr. Swan had three houses! One sticks in my mind as a possible site for this activity, and that house is still standing. 579 Washington Street features two buildings on the lot. Built circa 1850, one was a boot shop owned by members of the Randall family. The other building was a home for Dr. Swan. Both buildings stood next to the Morse Thread Mill building, and at one time they were used as storage for the mill. If one looks at the stories of who may have been involved in helping escaped slaves, these two buildings bring it together: a collaboration between the Swan and Morse families, both of whom had the financial and physical means to provide help to those seeking freedom. Below is a photo taken just after the Civil War, with the Randall Boot Factory on the left, and the Swan House on the right. I have included a photo of the site today. The buildings are in good condition, having been renovated to living quarters in the early 1980’s. Here, at long last, we have our Underground Railroad in Easton. Until next week, stay well. Frank  Randall Boot Shop and Swan House, c. 1870 Randall Boot Shop and Swan House, c. 1870  Randall Boot Shop on left, Swan House partially hidden by trees on right. Randall Boot Shop on left, Swan House partially hidden by trees on right. Hello all! Yes, this is a day early and with good reason!

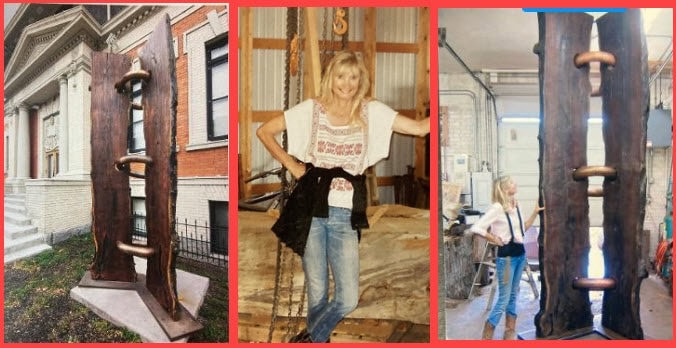

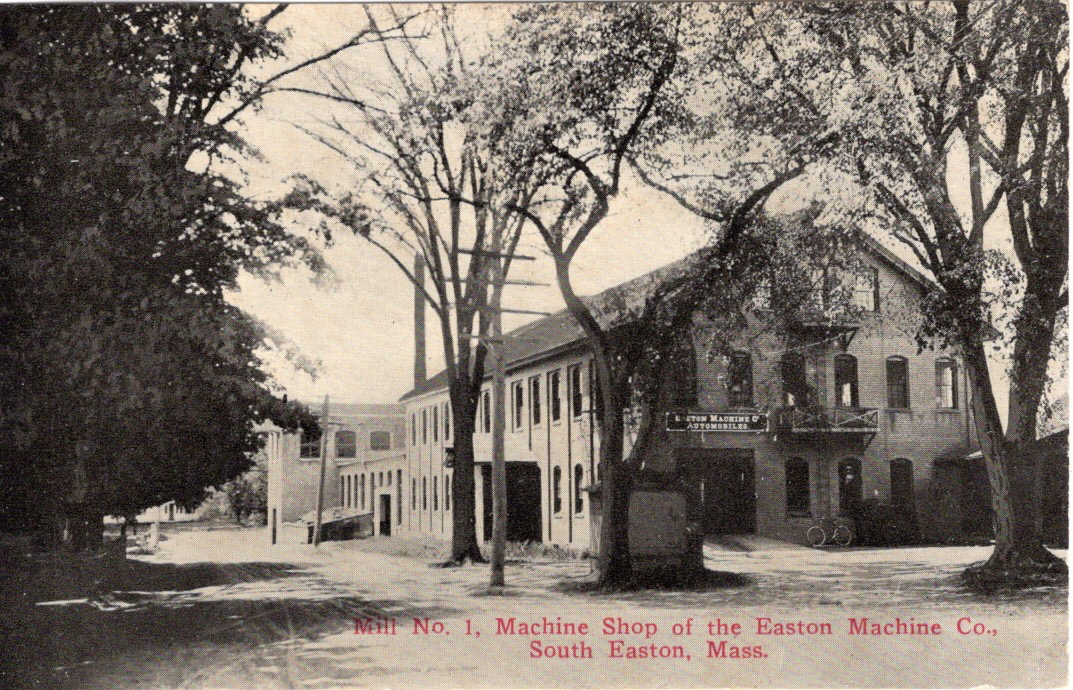

Our Open House this Sunday, July 10, will feature a very special celebration of Frederick Law Olmsted's "Forgotten Emerald Necklace" in North Easton. This year, Olmsted would have turned 200 and celebrations of his work will take place across the United States. We want to do our part to recognize this genius of place and space and his work here. There are two periods where Olmsted is involved in transforming North Easton. In the early 1880's, working closely with architect Henry Hobson Richardson, Olmsted used his talents in several familiar places: The Old Colony Railroad Station, The Rockery, Oakes Ames Memorial Hall, and the Frederick Lothrop Ames Gate Lodge. Work was also done at Langwater and possibly Queset around this period. In the early 1890's, Olmsted could be found working on the Ames Estates Springhill and Sheep Pasture, as well as the estate of Hobart Ames. The later work is influenced by the growing involvement of his children as the senior Olmsted was busy with the World's Fair and beginning to show a decline in his faculties with advancing age. There are two ways to discover Olmsted's work this Sunday. The Museum will feature an exhibit of his work in town, with an emphasis on Springhill. The best way to experience Olmsted is through a walking tour conducted by our own Ed Hands. This two-part tour will begin promptly at 1:30 p.m., departing the Museum for a walk to the Governor Ames Estate and Langwater. You will return to the Museum for some refreshments, then depart again for a trip to the Rockery and the Oakes Ames Memorial Hall. We are very grateful to Oliver Ames and the Ames Family for arranging for the Society to tour the landscape at Langwater. The Museum will be open from 1-5 p.m. Next, we have a very special announcement from our friends at the Ames Free Library, with thanks to William Ames: The Ames Free Library is pleased to announce that a new sculpture will be installed early next week on the library's campus. Sculptor Phoebe Knapp, of Billings Montana, created 'Tablet' in 2004. The statue stands 12 feet in height, and is made out of walnut, metal, and copper coated black iron pipe.' Tablet' resembles an open book, and was chosen to represent the importance and lasting grandeur of the written word. It will be placed outside of the Ames Free Library at the west end of the Children's room. The wood is from walnut trees planted along the El Camino Real in California starting in the late 1700s and cut down for various reasons in the early 2000s. El Camino Real is a 600-mile commemorative route connecting the 21 Spanish missions in California along with a number of sub-missions, four presidios, and three pueblos. Its southern end is at Mission San Diego de Alcalá and its northern terminus is at Mission San Francisco Solano The installation is made possible by the generosity of two Easton residents who left funds in their estate plans to the library: Elizabeth Ames and Warren Moffit. Elizabeth served as secretary of the Library's Board of Directors for 20 years, and Warren was a lifelong resident of Easton; he and his family were dedicated patrons of the library. On Thursday July 14th at 11:00 there will be a talk by the artist at the installation site and a reception afterwards at Queset House. We hope you will join us for this celebration of their wonderful generosity and of the arts here in Easton. Until next week, Frank Greetings, and a very happy Fourth of July to all! After a rainy start to the long weekend, it looks like it will be all fireworks, beaches, and barbecues on tap for Sunday and Monday! One of the dominant structures in South Easton is the former Morse mill located at 7 Central Street. Sharing a parking lot with Hennesey’s Package Store, the building serves as a landmark for directions to points south. It seems that many people know the building, but with our 1899 Morse Car now on display, it seems a good time to take a look back at that location and then take a look at the same area today. The Morse Privilege, so-called, really began with the arrival of E.J.W. Morse to South Easton in the 1820’s. He partnered with other people to produce cotton thread at various small mills around the area, probably using each of the smaller buildings to perform separate operations in the manufacturing process. This was not very efficient. By at least 1830 Morse moved a small mill from a nearby location (site of Stonehill College) and began to manufacture cotton thread at the Central Street location, very near the dam and the intersection of what is now Water Street. The business grew, and at one time it was the oldest cotton thread company in the United States. Around 1878, a second, larger mill building was added. This building was constructed of brick (the original mill, originally wood and expanded with other wooden structures over the years, stood at the west end of the new building). With a modern building able to hold modern machines, powered by steam and water, the company continued to thrive. Morse Thread was a trusted brand. The company developed, and patented, Silkateen, a thread which produced a silk-like finished product, as well as other inventions and improvements. After two generations, the company was sold to a major thread firm in England, and by the early 1890’s the building no longer was used to produce thread. A third generation Morse, Alfred Bryant Morse, around 1881 built a steam engine with two friends, William Hadwen Ames and Hobart Ames (on display at the Museum, courtesy of the Morse family) and built a larger, second engine a few years later. With an empty factory and lots of ideas (not to mention a high degree of mechanical aptitude and genius - Morse only completed the eighth grade before working in the business) Morse began a company called the Easton Machine Company. That machine shop began production of highly complex, specialized machinery for making lace, taffy, etc. A terrific fire around 1897 destroyed the old wood mill buildings, and heavily damaged the brick building. Morse rebuilt the brick building, extending it towards the dam, and continued production. Around this time, he took an interest in cars. He began tinkering with a prototype that became our Morse car, and even leased the building to the Cameron Brothers for a while as they began to develop their Eclipse steam powered auto. (This later company was undercapitalized, leading to a number of financial issues, moving around, and eventually failing. Another attempt by the brothers produced the Cameron car, again a short-lived venture.) Morse, with the success from his lace-making machinery and a yearly payment from the former sale of the thread business, was in a strong financial position to try car manufacturing. From 1902 to about 1917, several versions of his Morse Car were produced by the Easton Machine Company. The success of his car business, as well as other machine shop business, created a need for more Manufacturing space, so he built a new mill across the street, which later housed Crofoot Gear for many years. Our old photo is taken from a postcard. The caption “Mill No. 1” at the bottom indicates that the second building existed and dates this photo to around 1912. The brick thread factory is the main attraction here, well-maintained, and features the company sign prominently. Central Street runs alongside the building. A chimney rising from the rear indicates the location of a power plant for the factory. Along the front facade of the building, a large door was cut into the brick, and a cement ramp installed to allow automobiles to enter and leave the building. The second floor housed most of the machinery, and the first floor was used for assembly of the cars. Morse could make parts for other cars as well, so this became a very early repair garage for other people to have their early automobiles serviced. Note the peaceful trees that helped to shade the roads. Today, the building stands as a reminder of what once was. Covered with ivy, 7 Central Street now houses people rather than autos. During the Depression, the Morse family consolidated their business into Mill #2, and the old mill was sold to the Brockton Tool Company, who for decades produced plastic and rubber molds for the shoe industry. The 1980’s move by many American shoe companies to off-shore manufacturing left a hole from which the company could not recover, and before 2000 the building was sold. Today it remains a quiet reminder of two once-thriving businesses. Street lights, traffic signals, and stark pavement now surround the plant in the midst of a very busy intersection with Washington Street. For many years I worked right in front of the old car doors and cement ramp. Opening those doors on hot summer days provided at least a little respite from the heat inside the building. At the left of the new photo are a few trees on a lawn. When I worked at Brockton Tool in the 1970’s and into the late 1980’s, the people who owned the property across the street allowed the workers to have their lunch there every day under those trees, giving us a shady and cool place to eat before the factory buzzer went off and called us back inside for our afternoon shift. Until next week, stay well, and stay cool!

Frank |

Author

Anne Wooster Drury Archives

June 2024

Categories |

||||||

Easton Historical Society and Museum

PO Box 3

80 Mechanic Street

North Easton, MA 02356

Tel: 508-238-7774

[email protected]